Born in the United Kingdom, Tony Burton, a Cambridge University-educated geographer with a teaching certificate from University of London, first traveled to Mexico after spending three years as a VSO [Voluntary Service Overseas] volunteer teaching geography, and writing a local geography text, on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. From there his travels took him to Mérida in summer 1977, where he spent several weeks backpacking around southern and central Mexico, returning two years later to teach at Greengates School in Mexico City.

Over the next seven years, Tony traveled extensively throughout Mexico, visiting every state at least once, and organizing numerous four-day earth science fieldwork courses for his students. He co-led the school’s extensive aid efforts following the massive 1985 earthquake.

From Mexico City, he moved to Guadalajara, where he continued to organize short, residential fieldwork courses for a number of different schools and colleges and began organizing and leading specialist eco-tours for adult groups to destinations such as Paricutín Volcano, the monarch butterfly sanctuaries, and Copper Canyon.

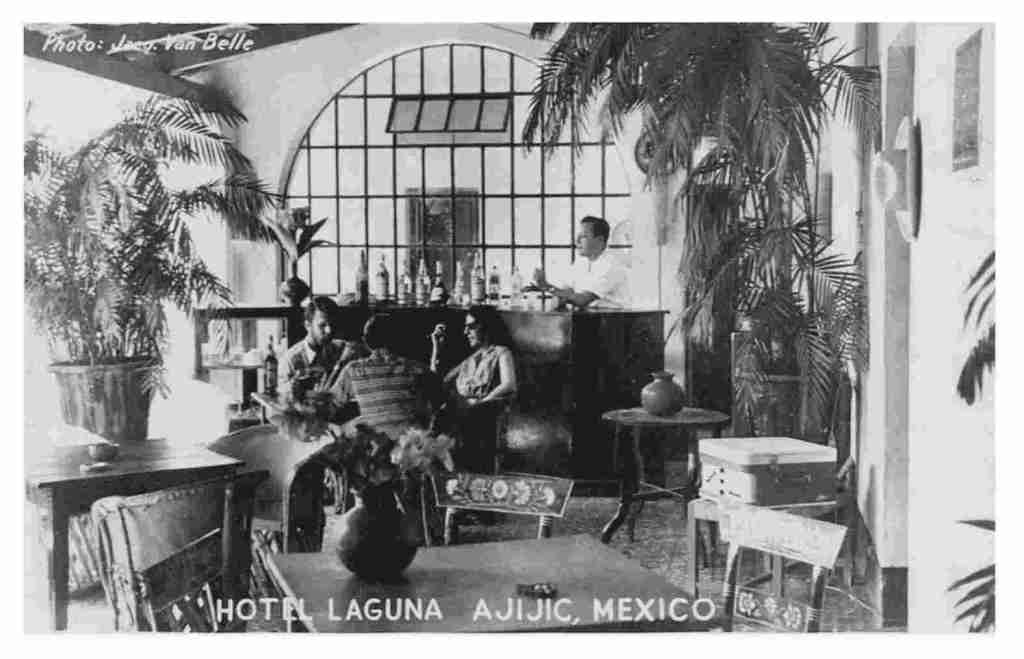

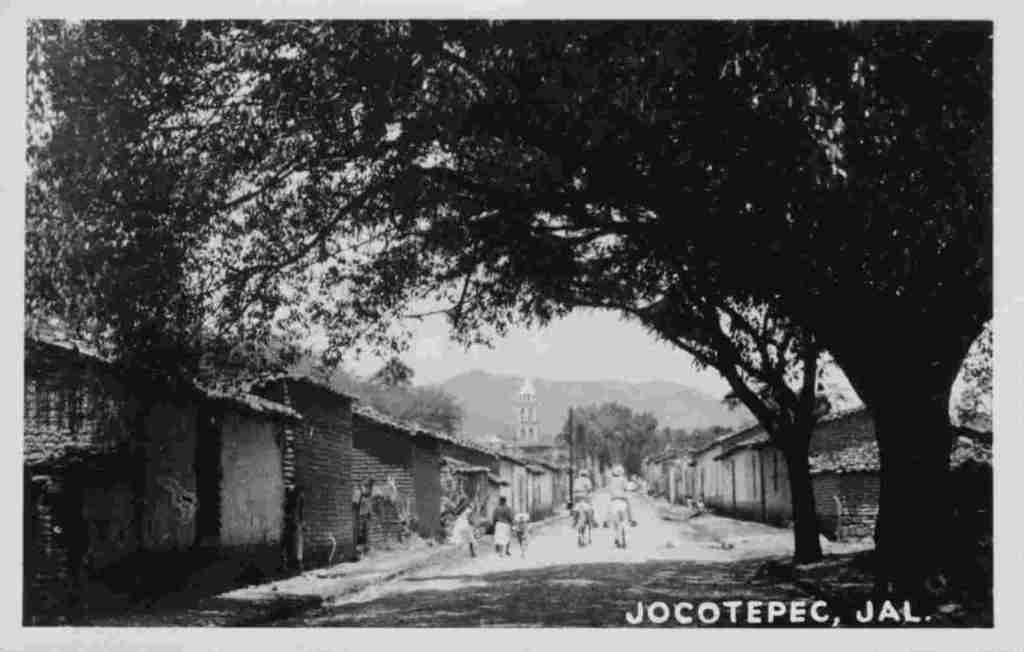

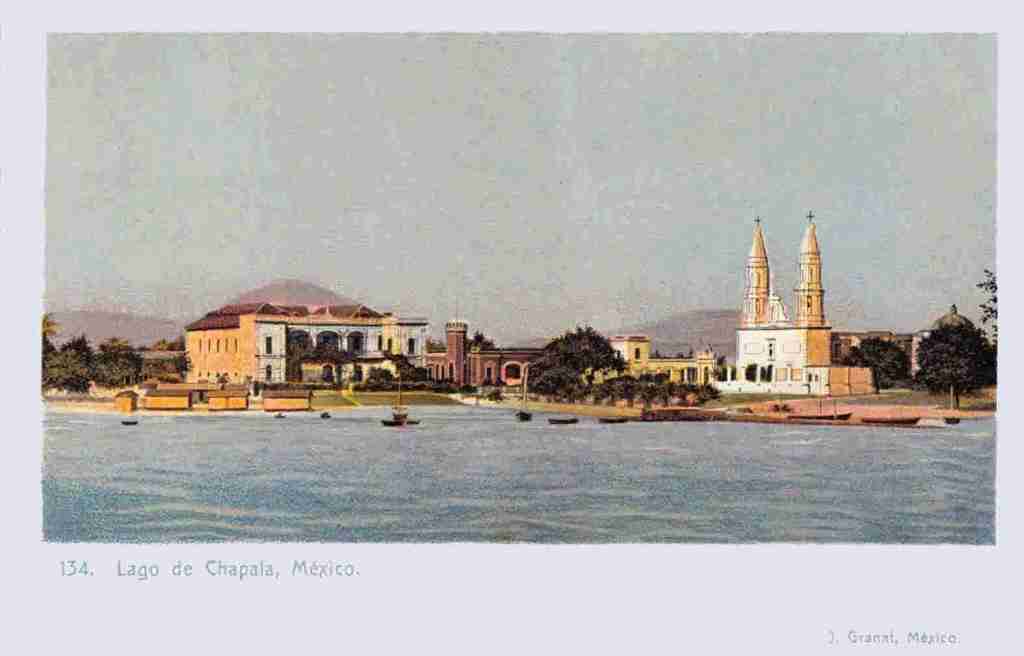

An award winning author, he’s written numerous books about Mexico including his latest Lake Chapala: A Postcard History (Sombrero Publishing). It’s part of a series he’s written on this region which is located about an hour south of Guadalajara. The 417-square-mile lake, Mexico’s largest, located in the states of Jalisco and Michoacán is situated at an elevation of 5,000ft in the middle of the Volcanic Axis of Mexico and is known for its wonderful climate, laid-back ambience, and is a popular destination for both travelers and ex-pats looking for a charming, low-key place to relocate. The three main towns along the lake are Chapala, Ajijic and Jocotepec. In an intriguing aside, Tony met his wife Gwen Chan Burton when she was working as at the director of the pioneering Lakeside School for the Deaf in Jocotepec. Gwen writes about the school and all that it has accomplished in her book, New Worlds for the Deaf, also published by Sombrero Books.

Tony’s other books about this region include Western Mexico A Traveler’s Treasury, illustrated by Mark Eager, now in its fourth edition; Mexican Kaleidoscope: Myths, Mysteries and Mystique, illustrated by Enrique Veláquez, and Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village. I’ll be covering them in upcoming posts.

Because I’m always interested in foodways, Tony was kind enough to share a copy of an undated Spanish language project put together by students from the Instituto Politécnico Nacional School of Tourism titled “Gastronomy of Jalisco.” It includes numerous recipes from the region including one for the famous Caldo Michi of Chapala (the recipe is below).

I had the chance to ask Tony, who currently is the editor of MexConnect, Mexico’s leading independent on-line magazine, about Lake Chapala: A Postcard History as well as the time he spent in this beautiful region of Mexico.

How did you first become familiar with Lake Chapala?

I first visited Lake Chapala in early 1980, on my way back to Mexico City from the Copper Canyon and Baja California Sur. Little did I imagine then that it would be where I would later fall in love, get married, and have two children!

What inspired you to write Lake Chapala: A Postcard History?

There is no single overwhelming inspiration. I realized, while living at Lake Chapala and writing my first books about Mexico, that a lot of what had been previously written was superficial and left many unanswered questions. In the hopes of finding answers, I decided to trawl through all the published works (any language) I could find, which resulted in Lake Chapala Through the Ages (2008), my attempt to document and provide context to the accounts of the area written between 1530 and 1910.

My next two books about Lake Chapala—If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants, and Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of a Change in a Mexican Village—focused on the twentieth century history of the two main centers for the very numerous foreign community now living on ‘Lakeside.’ Part of my motivation was to dispel some of the myths that endlessly recirculate about the local history, as well as to bring back to life some of the many extraordinary pioneering individuals indirectly responsible for the area becoming such an important destination for visitors.

Lake Chapala: APostcard History is my attempt to widen the discussion and summarize the twentieth century history of the entire lake area. Its reliance on vintage postcards makes this a very visual story, one which I hope will appeal to a wide readership, including armchair travelers.

What were some of the challenges you encountered in writing this book? Was it difficulty finding the numerous postcards you included? And doing the extensive research that went into the book? Are there any intriguing stories about hunting down certain postcards and any “aha” moments of discovery when writing your book?

The main challenge was in deciding how best to structure the material. Because of the originality of what I’m doing, it is impractical to follow the advice that writers should start with a detailed plan and then write to that plan! In my case, after collecting the information and ideas that exist, the challenge is to select what can be teased and massaged into a coherent and interesting narrative.

Because the postcard book is the product of decades of research, I had ample time to build my personal collection of vintage postcards, through gifts, auctions and online purchases.

There were many significant “aha” moments in the process: some concerned the photographers and publishers responsible for the postcards and some the precise buildings or events depicted. While I’m saving some of these “aha” moments–because they are central to a future book–one was when it suddenly dawned on me that wealthy businessman Dwight Furness was the photographer of an entire series of cards (Figs 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, etc.) that relate to my next response.

If you could go back in time to visit one of the resorts that is no longer there that you featured in your book, is there one that stands out and why is that?

Ooohhh; I’d love to go back to about 1908 and stay at the Ribera Castellanos resort (Chapter 6) during its heyday. While staying there, perhaps I could interview owner Dwight Furness, his wife and a few guests? Apart from a few ruined walls, Furness’ postcards of the resort are pretty much the only remaining evidence of the hotel. And perhaps one night I could invite local resident and prolific professional photographer Winfield Scott and his wife to dinner to hear their stories?

How long did it take to write Lake Chapala?

The writing took less than a year; but only because of the many prior years of research.

Since I often talk about food and travel, are there any culinary specialties in the Lake Chapala region?

Long standing culinary specialties of the area include (a) Lake Chapala whitefish (b) charales (c) caldo michi. And, when it comes to drinks, there is a very specific link to postcards. The wife of photographer José Edmundo Sánchez, who sold postcards ( Figs 7.5, 7.6 and 7.7) in the 1920s from his lakefront bar in Chapala, is credited with inventing sangrita, still marketed today as a very popular chaser or co-sip for tequila. (Chapter 7, page 74).

Is there anything else you’d like readers to know about your book?

I hope readers find the book as fun and interesting to read as it was to write!

MICHI BROTH

Ingredients:

- 2 tablespoons corn oil

- ¾ kg of tomato seeded and in pieces

- ¼ onion in pieces

- ½ kg carrot, peeled and cut into diagonal slices

- ½ kg of sliced zucchini

- 4 or 6 chiles güeros

- 100 gr. chopped coriander

- 2 sprigs of fresh oregano

- Salt to taste

- 2 ½ liters of water

- 1kg well washed catfish, yellow carp or red snapper

PREPARATION: Heat the oil and stew the vegetables in it, add water and salt to taste, let it simmer over low heat until the vegetables are well cooked, then add the fish and leave it for a few minutes more until it is soft.

Sangrita

I had the opportunity to stay at Tres Rios Nature Park, a 326-acre eco-resort north of Playa del Carmen and was first introduced to sangrita during my stay. I took several cooking lessons and learned to make a dish with crickets, but that is a different story. Chef Oscar also talked to us about the history of sangrita. The Spanish name is the less-than-appetizing “little blood” but hey, when you’re learning to grill crickets, you can deal with a name like that. The drink, as Tony writes in his postcards book, originated in Chapala in the 1920s.

Here is the excerpt:

”In the same year the Railroad Station opened, Guillermo de Alba had become a partner in Pavilion Monterrey, a lakefront bar in a prime location, only meters from the beach, between the Hotel Arzapalo and Casa Braniff,” he writes. “The co-owner of the bar was José Edmundo Sánchez. Regulars at the bar included American poet Witter Bynner, who first visited Chapala in 1923 in the company of D H Lawrence and his wife, Frieda. Bynner subsequently bought a house near the church. When de Alba left Chapala for Mexico City in 1926, Sánchez and his wife—María Guadalupe Nuño, credited with inventing sangrita as a chaser for tequila—ran the bar on their own. After her husband died in 1933, María continued to manage the bar, which then became known as the Cantina de la Viuda Sánchez (Widow Sánchez’s bar).”

Sangrita is typically used as accompaniment to tequila, highlighting its crisp acidity and helping to cleanse the palate between each peppery sip. According to Chef Oscar, the red-colored drink serves to compliment the flavor of 100% agave tequila. The two drinks, each poured into separate shot glasses, are alternately sipped, never chased and never mixed together.

Here is Chef Oscar’s recipe and below is one from Cholula hot sauce which originated in Chapala. Tony has a great story about that as well. More in my next post on his books.

For one liter of Sangrita:

- 400 ml. orange juice

- 400 ml. tomato juice

- 50 ml. lemon juice

- 30 ml. Grenadine syrup

- 20 ml. Worcestershire sauce

- Maggi and Tabasco hot sauce (mixed up) to taste

- Salt and pepper to taste

Mix together all the ingredients and serve cold. Suggested duration of chilling : 3 to 4 days.

Cholula’s Sangrita

- 1/4 cup (2 ounces) fresh orange juice

- 1/4 cup (2 ounces) fresh grapefruit juice

- 2 tablespoons fresh lime juice

- 20 pomegranate seeds

- 3 fresh sprigs of cilantro or to taste

- 1/2 stalk celery

- 3 teaspoons smoked coarse sea salt or sal de gusano, divided

- 1 tablespoon Cholula® Original Hot Sauce

Place all ingredients except salt in blender container, with about 1 cup ice cubes. Puree until smooth.Strain twice though a fine mesh sieve, discarding any solids.

Rim shot glasses with sea salt. Serve sangrita cold in rimmed shot glasses alongside your favorite tequila.